Copyright 101: Catching the Bug

Here's my article which was published this month in InSinC, the quarterly newsletter of "Sisters In Crime". I hope that you enjoy it and learn something along the way.

What the heck is © and what does it mean?

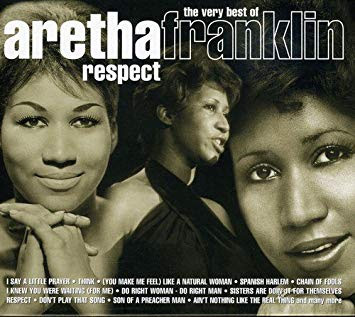

We see the symbol everywhere, on paintings, photographs, movie credit trailers,

magazines, CDs, and even on the Rights pages of books. Well, that little

copyright bug represents a powerful tool in the writer’s arsenal. This symbol protects

you, you heirs and your work from theft and infringement, and signifies that

you are the exclusive owner and author of the work.

Thanks to

visionaries like Mark Twain and James Fennimore Cooper, in 1909, the United

States enacted the first Copyright Statute, which recognized the necessity that

artist’s works be protected as their stock in trade. As the technological

advances in the publishing, advertising, music and entertainments industry have

blossomed, the law has been amended. The most radical revision occurred in

1976, which is the version that protects us today.

What does the Copyright Law accomplish?

The Copyright law protects a work, in our case a “Literary Work” (material

contained within a book, periodical, manuscript, phono-record, film tape, disk

or card), from the moment it is created. From the first letter you type on your

computer, or the first syllable penned on the page, your work is protected from

infringement. It makes no difference whether the work is published or

unpublished, both are entitled to equal protection under the law. In fact, any

derivation (abridgement, translation, etc.) of your work is protected as well.

You, alone, as the owner of your copyright, are entitled to reproduce, display

and distribute your work for the term of your life plus seventy years.

Who does the law protect? If you are

the original author and have not created a “work for hire,” you are an author

entitled to protection under the law. This means that you have not created the

work within the scope of your employment, or have not been commissioned for the

work. Under those circumstances, the copyright belongs to your employer.

Therefore, if you have been hired by a magazine to write an article, or by a

publisher to write a series like Nancy

Drew or The Hardy Boys, the work

does not belong to you and you are not entitled to file for copyright

ownership.

What exactly does the Copyright Law protect?

This is perhaps the most confusing aspect of the law. The statute states

that a “Literary work” is expressed in words, numbers or other verbal or

numerical symbols or indicia. Huh? In plain English, the statute covers your

words, your expression, and your creation as an author. It does not cover an

“idea”. For example, Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” is a story about

star-crossed lovers. Numerous artists, including, Leonard Bernstein’s “West

Side Story”, and Stephenie Meyer’s “Twilight”, E.L. James’s “Fifty Shades of

Grey” have reinvented this “idea” behind the tragedy. Each author is entitled

to individual copyright protection because they have reinterpreted this

universal idea into their own words. Tony and Maria’s racially charged, gang

related story set in New York City is different than the trope of warring

medieval Italian families. So, in summary, your written words on the page are

being protected, not the underlying idea. Generally, the law does not protect

ideas, unless they are designs, inventions or processes, which are covered by

the Patent Law.

Similarly, titles,

phrases and slogans are also not protected by the Copyright Law. Phrases like “With a name like Smuckers, it’s got to be

good,” and “Good to the last drop”

are protected by the Trademark Law, because they identify goods and services in

the marketplace.

Finally, the law

does not provide protection for works in the “public domain”. These are works

that are no longer subject to protection due to the expiration of their

copyrights, or the failure to meet a requirement of the copyright law, allowing

them to be used freely and without permission of the original copyright owner.

Shockingly, Dostoyevksi’s “Crime and

Punishment”, Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Dr.

Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”, Kafka’s “Metamorphsis”

and George Orwell’s “1984” all have

lapsed copyrights and are available to published and reprinted without

compensation to the writer’s estate. Entry into the public domain explains why

you can pick up the great classics by Jane Austin, Mark Twain and Jonathan

Swift for free on your Kindle and at Gutenberg.org.

There is one

exception where your work can be reproduced without infringement or

compensation, and that is called the “Fair Use” exception. So long as your work

is being used for educational, non-commercial purposes, the law does not consider

the inclusion of your work in research, scholarship, news reporting, teaching

and criticism, as being a copyright infringement.

How is the work protected? It’s unnecessary

to register, or deposit, your work with the U.S. Copyright Office at the

Library of Congress in order to benefit from the protection of the law,

however, there are several advantages to doing so. First, the date of your

creation will be proof positive that you are the first in time to write your

particular story. Second, if someone else writes or copies the identical story,

this filing will help with the statutory enforcement of your rights and

remedies against the infringer. Third, it’s really cool to have that Copyright

Certificate of Registration hanging on your wall. It’s worth the thirty-five

dollars invested in the filing fee to stake your claim on your brilliant work

of art, and it’s easy to do online at www.copyright.gov.

Be forewarned, there’s a backlog of filings, so you must be patient. It may take

six to eighteen months to receive your certificate.

Besides filing

your work with Copyright office, you must indicate to the world that you are

aware of your rights in your work. We have come full circle back to our little

copyright bug, ©, which must appear on your work, preferably your title page. If

your work is published, the correct way method of implementing the symbol is: ©

year author’s name, i.e.; © 2016 Jodé Susan Millman. If your work is

unpublished, the correct for is Unpublished Work © 2016 Jodé Susan

Millman. If you place this notice on

your work, the world will be informed that you have protected yourself, and the

notice can be used as evidence against any infringer.

What are the remedies for infringement

under the law? If someone uses your work without compensating you or

without your permission, that act is in violation of your exclusive ownership rights

under the Copyright Law. You will be entitled to an injunction, actual damages

and loss of profits, the infringer’s profits, attorney’s fees, and statutory

damages as permitted by the law. The infringer may also be subjected to

punishment for criminal infringement if they used your work for commercial

gain.

This thumbnail

sketch highlights the writer’s basic copyright protections available under the

voluminous U.S. Copyright Statute, and the statute, filing information and

additional references can be found at www.copyright.gov.

The takeaway is

that your precious literary masterpiece is protected from the moment of

creation. Don’t be afraid to catch this © bug, it will immunize you, your work

and your heirs from the literary pirates of the world.

Jodé Susan Millman

is an attorney practicing in New York’s Hudson Valley. She is a member of the

EASL Section of the NYS Bar Association and was a contributing editor to the Kaminstein Legislative History Project

analyzing the Copyright Law of 1976. She is also the author of the theatre

guide, SEATS: NEW YORK, published by

Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, and her first unpublished thriller novel, “The Midnight Call”, won Best Police

Procedural from Chantireviews.com and was short-listed for the Clue Award in

2014.

Comments

Post a Comment