Right of Publicity: Naming Names

In my last article, I discussed Copyright basics. I’d like to reiterate that just as someone else must obtain permission from you to reproduce your work, you must similarly oblige. Let’s say that you have a scene where your heroine is serenading the hero on guitar with “Just The Way You Are” by either Bruno Mars or Billy Joel. In order for you to use any lyrics from that song in your novel, you must get permission from the copyright owner (Billy or Bruno) unless the material is in the public domain and not subject to copyright protection. This is true even if you give them attribution. Licensing music lyrics can be awfully expensive, so you’re better off naming the song title for free than paying them all of your royalties. The same rule applies to text or quotes.

Generally, works published before 1923 are in the public domain, and the status of copyrights works between 1923 and 1964 can be searched at Stanford University’s Copyright Renewal database, https://exhibits.stanford.edu/copyrightrenewals. A complete copyright search can be performed at the Copyright Office, copyright.gov.

What about using the names of people in your book? Suppose you’re writing a novel about your character’s elicit love affair with Elvis Presley or Jimi Hendrix or Elon Musk. Do you need their permission to name names? Interestingly, this is not a copyright issue. Rather, this question concerns two different rights – the right of privacy and the right of publicity.

The right of publicity is a right that we all possess in the commercial use of our name, likeness or picture. If you want to produce mugs with the words “World’s greatest Author” beneath your photo, you or your licensees have the right to do so. Only you have the right to the commercialization of You for as long as you live. In the case of Elvis or Jimi, you have the right to use their names in your works because the dead do not possess the right of publicity under New York State’s Civil Rights Law.

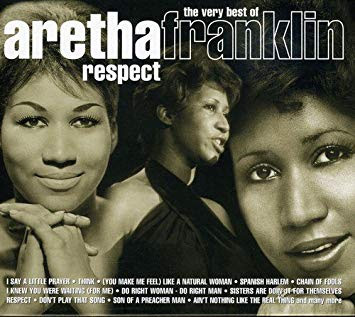

That’s my jurisdiction, but conversely, California treats someone’s likeness and image as a property right. Thirty years after John Lennon’s death, Yoko Ono was still suing a bar in Scotland themed after her husband. As you can see, it’s one of those funky laws that changes from state to state, so check our your laws before naming dead people in your novel. However, you would need their estate’s permission to put their photo on a mug or tee shirt or the cover of your book.

Paula McLain is an example of an author who has written several bestsellers reimagining the lives of famous deceased women such as Hadley Hemingway, aviator Beryl Markham, and war correspondent Martha Gellhorn in “The Paris Wife”, “Circling the Sun”and “Love and Ruin,” respectively. No permissions were required since her subjects were not alive at the time of publication. However, in the case of Mr. Musk, or any living person who you intend to mention in your novel, it’s best to get permission to use his name.

Recently, a friend asked me whether he could license a photograph he’d taken in the 1980’s of a now infamous entertainment mogul. The guy is still alive and kicking, so my answer was an unequivocal “No”. In order for my friend to sell his photo of Mr. W, he’d have to get Mr. W’s permission, and the odds of that are unlikely. Only, Mr. W can profit from his photo, likeness or name even though he is considered to be a public figure.

The right of privacy is held to a different standard. While not specifically created by law, the Supreme Court has been interpreted the right to exist in order to prevent the government’s unwarranted intrusion in the issues of marriage and birth control. Anyone who has seen the wonderful movie, Loving, understands this point. However, the right of privacy is closely related to the First Amendment’s protection of the freedom of the press and the laws of defamation.

If you base a fictional character on a real person, generally, the public disclosure of private facts is prohibited. So, if you’ve woven an intimate fact about Mr. Musk’s sexuality, family life or medical conditions into your manuscript, which are not a matter of public concern, watch out! You could be the next Star Man spinning around the planet. You are permitted by law to disclose only matters of public knowledge.

And if in your novel, you include information about Mr. Musk, knowing that it is untrue and holds him up to ridicule, public contempt or disgrace, you may be subject to prosecution under the defamation laws. There are two types of defamation: a) Libel is the written act of injuring a living person’s reputation, and b) Slander is the spoken act of defamation. Public figures are held to proving a higher standard of injury as they must show that the statement was made with actual malice.

In order for a plaintiff in a fiction-defamation lawsuit to win, they must prove that the publisher and author of a defamatory statement knew or should have known that the “fictionalized” character was objectively identifiable as the real person. In other words, the details of your character must be so closely aligned that someone who knows that person would have no difficulty linking the two together. So, if you want to want to base your fictionalized character on Mr. Musk, or any living public figure, do your homework and go big or go home. Merely changing the name is not enough. Make certain that if you’re getting real, that your character is so outrageously over-the-top that no one could possibly believe that your fictionalized character was intended to be factual.

A great example of conflating fact with fiction is the bestseller “Primary Colors.” This was a thinly veiled novel depicting Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential run. Originally published by an anonymous author, the columnist Joe Klein was ultimately unmasked as the novelist. At the time, this proved to be an effective marketing strategy, but with today’s social media, this stunt wouldn’t stand a chance.

It wouldn’t hurt to add a disclaimer, which although self-serving, may support the defense that the identification of the real person is unreasonable. It should appear on the reverse title page of your novel, or be skillfully integrated into either the introduction or preface of your book. Placing the subtitle “A Novel” also helps. Most important, if you truly have questions about a potential defamation case, contact your attorney.

Taylor Swift has made a career out from writing masterful lyrics about old boyfriends without naming names. And we are all still trying to figure out whether Warren Beatty or Mick Jagger was described in Carly Simon’s “You’re so Vain.”

Keeping your readers guessing is half of the fun of writing and with a bit of creativity, you can do it too without naming names.

Comments

Post a Comment