Copyright Royalties : No R-E-S-P-E-C-T

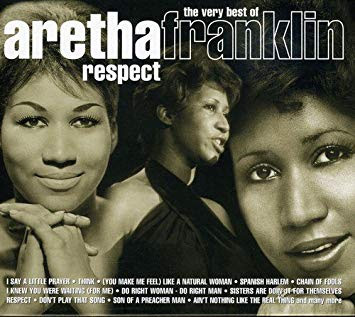

The recent passing of Aretha Franklin has highlighted the issue that artists, whether they are musicians, visual artists or writers, truly get no R-E-S-P-E-C-T in terms of statutory royalties due under the copyright laws. When Ms. Franklin died in August, her cry of empowerment, “RESPECT”, had been played over seven millions times on American radio stations, and she’d never received a penny for any of these performances. That’s because under the copyright law, only writers and publishers of musical compositions, in this case, Otis Redding, are entitled to receive royalties.

One major impediment to receiving compensation is that the copyright law has been weak in keeping pace with technology. In the 1990s, Congress passed a bill to allow performing artists to collect royalties from internet and satellite radio, but songs recorded before 1972 were exempt. In 2014, the “Respect Act” (Respecting Senior Performers as Essential Cultural Treasures Act- named with the blessing of Aretha Franklin) was designed to remedy the problem by requiring that digital music streaming services pay the same royalties as terrestrial radio for songs prior to 1972. The act was referred to committee and it died there. However, in January 2018 the “Music Modernization Act” was introduced to accomplish the same goal, passed the House and was referred to Senate Judiciary Committee for review. Unfortunately, the law only protects the copyright owner, not the artist.

In January 2018, General Motors was sued by Adrian Faulkner (aka Smash 137), a Swiss graffiti artist, for using one of his art pieces in an ad campaign called “Art of the Drive”. Graffiti art is entitled to copyright protection, but GM claimed that since the artwork was installed and displayed on a parking garage, it was actually an architectural work which is exempt from copyright protection. The matter is pending before the California federal courts to determine whether Mr. Faulkner is entitled to payment from GM for the use of his art.

How do Aretha’s and Mr. Faulkner’s sad stories relate to writers? Because, similar to musicians, we are faced with the issues of contractual and copyright royalties which are sorely out of date.

In publishing, an advance is a lump sum amount that is paid to the writer before the book is published, and is credited against income due to the writer by the publisher as royalties for the sale of a book. Usually, one-half is paid at the time of the signing of a publication contract and the balance is paid upon the acceptance of the manuscript. Many factors are calculated into the size of the advance, such as the success of the last book, the topic, and author’s reputation. For example, last year the Financial Times reported that Michelle and Barack Obama had scored more than $65 Million for the rights to their memoirs and books deals. The previous record, $15 Million, was held by Bill Clinton for is 2004 memoir, My Life.

The advance is the writer’s hedge against poor book sales as generally there is no repayment of unearned advances back to the publisher. Mr. Clinton had no worries as his book sold a record 400,000 copies on the first day, and neither to the Obamas based upon their track records.

Today, many independent publishers are opting to offer the writer a greater share of the profits as substitute an advance. This spreads the potential loss between the writer and publisher, and makes the arrangement much more of a partnership between the two.

Royalties are a payment made by the publisher to the writer for each copy of the book that is sold. This is a key term that is negotiated in the Publishing contract between the writer and the publisher, and it is usually paid on the “net price” of the book rather than the “list price”, or cover price. This means that the royalty is calculated after the deduction of the publisher’s expenses discounts to the bookseller or wholesaler. Often there is a discount of 40%, so if a book retails for $14.99, after subtracting the 40% ($6.00), the royalty will be paid on the balance, $8.99.

The Writer’s Legal Guide: An Author’s Guild Desk Reference (4th Ed.) and Model Book Contract, www.authorsguild.org, set forth schedules for standard royalty payments for trade, deep discounts, trade and mass market books starting at 10% of the retail or list price, and more established authors can often obtain better terms as high as 15%. New writers should beware that it is often difficult to obtain the 15% upon the “list price”.

In contrast to the contractual royalties, there are statutory royalties due to the writer under the copyright law. However, there are several huge provisos. First, under the copyright law, the “Fair Use” exception permits the free use of the work without permission of the author or copyright owner when it is used for educational, criticism, comment, news reporting, scholarship or research.

It is not “fair use” to copy or use the work for a commercial motive in the educational setting, such as the inclusion in a textbook or classroom lessons, unless the material is in the public domain. For example, if a high school English class is reading a portion of Elie Weisel’s Night, and the teacher includes excerpts in their materials, a copyright license fee is due Mr. Weisel’s estate for such use. To qualify as “fair use” the use should be spontaneous, like making a photocopy for research, not widespread dissemination of the materials.

Another issue is the mechanism for monitoring the collection of the statutory copyrights monies due an author. Although the nature of our writing makes us all amateur detectives, it would be virtually impossible to locate every magazine, newspaper, school, or Internet site that has used our work. Fortunately, the Authors Registry, www.authorsregistry.org is a clearinghouse designed to monitor the use of literary works, collect the fees due U.S. resident authors and distribute them. To date, they have collected and distributed over $30 Million in statutory copyright license fees to U.S. writers.

Many literary agencies and organizations such as Sisters In Crime, Mystery Writers of America, and The Authors Guild are enrolled with the registry, allowing their members to obtain a free listing in the registry. Once an account is created, the registry will not only collect the fee but they will maintain the necessary tax records of the transactions. They charge a minimal 7.5% commission for the money they distribute.

As authors, we are extremely fortunate that the Authors Registry exists, and as members of Sisters In Crime, we should take advantage of the free listing to protect our rights and collect our statutory royalties.

Similar to visual artists, writers are not entitled to any resale royalties of books. In July 2018, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco ruled that visual artists can no longer receive royalties for the resale of their works in California and invalidated the California Resale Royalty Act for art sales conducted after the 1978 effective date of the Copyright Act. In “The Estate of Robert Graham, et al vs. Sotheby’s Inc.,” artists Chuck Close and Laddie John Dill filed a class action lawsuit against Sotheby’s for failing to pay royalties under the California act. The court held that the state law was in conflict with the 1978 copyright law’s first sale doctrine, which provides that once a copyright owner sells the work for the first time, they lose control over future sales.

While massive, wall-size paintings like Chuck Close’s are different than a standard book, the same restriction applies to writers. Recently, a friend discovered a first edition of Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood” in her bookcase. An appraiser valued the book at $6750.00. While she does not intend to sell the book, if a resale law existed, she would owe the Capote estate a nice chunk of change upon any sale of the volume.

Aretha’s passing should be a call to arms for all artists. Whether we are painters, sculptors, clothing designers, graffiti artists, playwrights, musicians, songwriters or writers, we work hard to bring works of personal expression into the world. As writers, we possess contractual rights that can be negotiated with publishers and we have statutory rights that exist from the moment of creation. Those rights should not be taken for granted and we should do everything within our power to protect, preserve and receive their benefits due under the law.

Perhaps, we should use the power of words to become more vocal and assist all artists to expand their rights under the law as well.

Comments

Post a Comment